5 Methods of Risk Control for Life Science Products

Of all the dynamic aspects of life science product development, risk management is one of the most important. From an organizational standpoint, controlling risks associated with your products protects your business interests; likewise, it ensures higher levels of care and safety for patients and users. When done in an iterative fashion from the start of development, thorough risk control can have significant impacts on your products, services, and organization.

When it comes to risk control, there are five key avenues of approach: avoidance, reduction, monitoring, transference, and/or assumption. These approaches often work in concert with each other, but each have their own benefits and strengths in the risk management process worth accounting for in your product development.

Avoidance

Constructing controls that result in avoidance of risks is one of the best approaches to managing risk. It usually involves eliminating or reducing the identified risk through adjusting product requirements. Through this method, exposure to hazards, hazardous situations, and harms are essentially bypassed before they present an issue to patients and users.

Constructing controls that result in avoidance of risks is one of the best approaches to managing risk. It usually involves eliminating or reducing the identified risk through adjusting product requirements. Through this method, exposure to hazards, hazardous situations, and harms are essentially bypassed before they present an issue to patients and users.

Risk avoidance relates to FDA’s safety by design principle. Through this principle, FDA expects that your product design is adjusted to make it inherently safe and effective. This can often entail making sure that:

- Use-related hazards have been identified and eliminated or minimized as much as possible

- Analytical methods have been used for identifying, assessing, and controlling hazard risks

- Critical safety characteristics have been identified and designed into the product

By demonstrating these factors have been thought through when you submit your product for regulatory review, it can provide FDA greater assurance that your team’s primary concerns are patient and user safety. However, it presents challenges when it comes to your product design; if the risk control changes one or more fundamental product requirements or necessitates significant investment of time and resources to incorporate, this can negatively impact project timelines. Therefore, when using the avoidance approach, it’s beneficial to begin risk management activities earlier on in the development process.

Reduction/Mitigation

If a risk cannot be designed out of a product and avoided entirely, it must be reduced or mitigated to acceptable levels. This may be the most common approach to risk management in life sciences, and this is reflected in both regulatory guidance and international standards. Between FDA’s Q9 Quality Risk Management guidance and ISO 14971, the importance of risk reduction is clearly laid out for manufacturers.

When it comes to acceptable levels of risk reduction, FDA does not offer a solid definition nor clear guidelines on their expectations. Rather, they rely on their product classification regulations and recommend best practices for life science organizations to guide thinking and solid, evidence-based judgment on risk acceptability. Meanwhile, ISO 14971 advocates for risks to be reduced to a level “as low as reasonably practicable” (ALARP) to be considered acceptable. The ALARP principle takes into account relevant standards, applicable national/regional regulations, identified stakeholder concerns, and the generally accepted state of the art of life science products in order to make a solid determination on risk reduction needs.

Monitoring

Sometimes, life science products risks are contextual; hazards and hazardous situations can present in different use scenarios dependent upon environmental factors and usability variables. In the event a context-dependent risk cannot be adequately designed out of the product, the next best approach is monitoring. This approach is also vital for risks that cannot be fully reduced and some assumed level of risk must remain as result. To control both of these concerns, monitoring can be an effective approach.

Sometimes, life science products risks are contextual; hazards and hazardous situations can present in different use scenarios dependent upon environmental factors and usability variables. In the event a context-dependent risk cannot be adequately designed out of the product, the next best approach is monitoring. This approach is also vital for risks that cannot be fully reduced and some assumed level of risk must remain as result. To control both of these concerns, monitoring can be an effective approach.

Risk monitoring can take many different forms. If a risk cannot be designed out, and all other reasonable attempts to reduce it have been made, then controls that confirm monitoring once in the hands of consumers is vital. This is often demonstrated in postmarket surveillance, an integral part of the product life cycle. Some other controls that could be implemented for monitoring include:

- Consumer reporting tools (web platforms/portals, etc.)

- Customer support

- Other feedback channels for CAPA/remediation

- Interconnectivity/integration with monitoring software tools

- Labeling with warnings for context-dependent risks

- Routine risk-benefit analysis in the postmarket environment

- Regular reviews for identification of new or shifting risks

While this is not an exhaustive list of risk monitoring strategies, these examples serve as a starting point for all the options available to your life science organization. These types of controls are no doubt constrained by time, cost, and scope, so identifying which ones are most effective and practicable is key.

Transference

Risk transfer is an approach used by many life science organizations to essentially offload product risks to other parties. While not entirely common, transference does have its opportunities and benefits for managing the risks of your product. It should only be undertaken when both sides (your organization and the external party) have a solid understanding of the benefits of the product versus its risks. Other parties need to have skills and knowledge related to the product and its risks for appropriate accountability, authority, and responsibility to be assigned to them. In addition, these parties must be willing to accept these risks in the first place.

There are numerous ways risk can be transferred. Whether through insurance, contracts, or agreements with specific requirements outlined for other parties, risk can be adequately communicated, accounted, and taken responsibility for. However, while this seems like a simple approach to dealing with risk, it’s neither an entirely viable approach for life science organizations, nor is it always appropriate. Especially because FDA insists on safety by design, regulators look for evidence that risks have been adequately designed out of your product. Offloading risk rather than making good faith efforts to manage it may not convince reviewers of your product’s safety and effectiveness. As a result, risk transfer should be examined as an option when other avenues of control and mitigation cannot provide adequate assurances of safety and efficacy.

Assumption/Acceptance

Sometimes spoken of as the “last resort” in controlling risk, assuming or accepting a risk is not a decision that’s easily made. All attempts to reduce or avoid the risk altogether must be made, as regulators want to see evidence of those attempts as part of your premarket submission. Otherwise, it’s likely reviewers will not accept your submission; good faith efforts to control risks as much as possible are expected by FDA and other regulatory agencies.

Sometimes spoken of as the “last resort” in controlling risk, assuming or accepting a risk is not a decision that’s easily made. All attempts to reduce or avoid the risk altogether must be made, as regulators want to see evidence of those attempts as part of your premarket submission. Otherwise, it’s likely reviewers will not accept your submission; good faith efforts to control risks as much as possible are expected by FDA and other regulatory agencies.

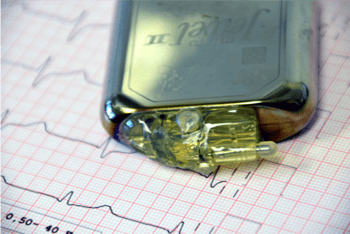

Now, there are plenty of cases in which risks cannot be designed out of a product, and for good reason. For example, implantable medical devices such as pacemakers require major surgery for use by patients. The risks of surgery are influenced by the patient’s prognosis, sterility of the operating environment, the surgeon’s skill level, any other comorbidities the patient experiences, and so on. This leaves a critical gap between safety and effectiveness that has to be bridged; in order to get treatment, the risks of the surgery have to be assumed. And many of the ancillary risks not under the manufacturer’s direct control can be mitigated through other avenues such as labeling, instructions for use, and so on.

Risk Controls and Risk-Benefit Analysis

Striving to manage assumed risks and any others associated with it ultimately results in an important aspect of regulatory submissions: risk-benefit analyses. Demonstrating that the benefits of a life science product outweigh whatever residual risks that remain—assumed, transferred, reduced, monitored, etc. —is important in identifying acceptable risks and ensuring product safety and effectiveness. This process, while not expressly required by FDA and other regulatory bodies, is nonetheless a vital part of the compliance process.

In an ideal world, all risks could be designed out of a product entirely; unfortunately, such a world does not yet exist—and maybe never will. There’s no mistake that technology is rapidly changing the risk profiles of many life science products out there, increasing benefits while decreasing risks. For example, advances in laparoscopic technologies have made procedures like bariatric surgery far less dangerous, more rapid-paced in terms of recovery, and more accessible to patients beyond the traditional risk parameters, all without sacrificing the benefits of the treatment. Changes like these are vital in expanding treatment options and improving patient outcomes.

When it comes to controlling the risks of your life science product, there are many avenues of approach. Whether your teams work to certify risk is adequately transferred to appropriate parties or reduced in accordance with ALARP principles, the spectrum of risk control in modern life science product development is vast. Leveraging all available methods to your advantage can result in more robust and effective risk control throughout your product’s life cycle.

About Cognition Corporation

At Cognition, our goal is to provide medical device and pharmaceutical companies with collaborative solutions to the compliance problems they face every day, allowing the customer to focus on their products rather than the system used to create them. We know we are successful when our customers have seamlessly integrated a quality system, making day-to-day compliance effortless and freeing up resources to focus on product safety and efficacy.